Cold Chisel play a secret show in Marrickville, Sydney

There’s a dirty orange sun sinking over Marrickville. After two months of bushfires and smoke haze, another heatwave is coming our way. Soon 2019 will be over. The fires, the atmosphere, the time of year, intensify that melancholy feeling things are ending. But the slightest breeze in the afternoon connects me to a sixth sense there might still be some magic left in the world.

At a venue called The Factory, I join an unusually busy line-up for an obscure band called The Barking Spiders. My wrist is stamped with what looks like a bird’s wing – and in I go, to a not-so-secret warm-up show by the legendary Australian group, Cold Chisel.

Raceways, wineries, stadiums, sports events… these are Cold Chisel’s more usual stomping grounds these days. The band have just released Blood Moon, their ninth album, and are gearing up for what is touted, surprisingly, as their first-ever open-air summer tour. A highlight to come will be a huge show on Glenelg Beach in Adelaide, the town in which they formed, where thousands will welcome them back despite swirling winds and baking summer heat.

Tonight is the dress rehearsal. Blood Moon is already being acclaimed as the band’s best album since the brightly produced, pop-inclined East (1980) and the ranging, muscular musical terrains of Circus Animals (1982). It could have appeared as a bridge between those two classics, though a nagging feeling persists this new recording is just a few songs shy of a truly great album.

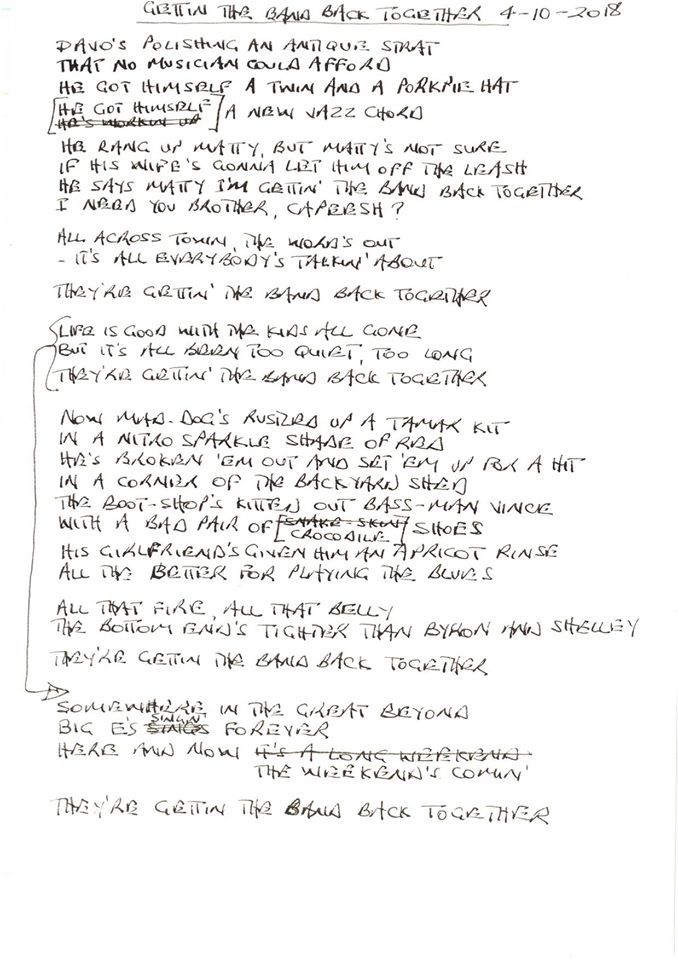

As always, the songs have the most power when the details in them get particular. The first single, ‘Getting the Band Back Together’ comes on with the confident swagger of old, and a typically suggestive criminal couplet: “Davo’s polishing an antique Strat / that no musician could afford.” ‘Drive’ operates off the same ambiguities, “A little speed is what I need.” ‘Accident Prone’ is likewise full of excuses that you know the protagonist barely believes himself. ‘Killing Time’ is close to being operatic, seething with the energy of a mutually terminated relationship, exposing the murderous absolutes necessary to get the job done, with drought on a farm serving as the metaphoric landscape for a couple’s point of no return. Pleasure, morality, love, the law, the road, freedom… we’re moving across boundaries and doing what we want, can or must.

At a press conference back in November for the new album and tour, the band’s “match fitness” is questioned. Singer Jimmy Barnes is feisty about having to assure everyone they will be ready. It’s been four years since their last album, The Perfect Crime, and the live shows that went with it. Deep down, Barnes knows Cold Chisel’s Mac truck intensity needs a test run to make sure the engine is in full working order.

The irony for big bands like Cold Chisel is that small venues, up close and personal, can push them in ways spectacular settings often don’t. Despite a savage bush fire season, and at least one show cancelled in the elemental horror of it all, the band will play on to titanic audiences and zealous responses the likes of which only giant acts can achieve.

I’ve seen Cold Chisel now over 30 times. You won’t be surprised to hear that after I passed the 30 mark, I let my tally-keeping slip. Despite that, I can safely say this early secret show in Marrickville will only be second time I’ve seen them in the last three decades.

Almost all the fanaticism I exhibited was during Cold Chisel’s first grand phase from 1976 through to 1983, or from when I was around 16 years of age till I turned 23. Yes, I saw some very big shows towards the end, but I always liked them best in a tight ring.

Nowadays, there’s a revisionist tendency from critics that sees bands like Cold Chisel as hegemonic FM-radio entities to be rebuffed or even expelled. This is history upside-down. Back in the day, no one was playing them or Midnight Oil on the commercial radio I was hearing. These bands succeeded by punching their way through, getting so big on the live circuit they could no longer be ignored. It’s fair to say they not only shifted the dial on radio for Australian content, they helped change how venues were being booked, and together with the varied likes of Dragon, The Angels and Rose Tattoo demanded more space for creative local acts that convincingly reflected their audience’s lives.

My hometown of Newcastle has always had a proud hand in supporting tough, smart rock n roll bands. There’s no doubt Newcastle was essential to the early survival and success of AC/DC, Cold Chisel and Midnight Oil. AC/DC filmed their first video for ‘Jailbreak’ there; Chisel and the Oils were so frequently in town they became embedded as local heroes.

The fact huge workers’ clubs and hard-drinking, jam-packed surfie pubs were just two-hours’ drive north of Sydney helped make Newcastle very appealing and profitable to visit. Venues like the Mawson Hotel, Swansea Workers, Belmont 16’ Sailing Club, Wynns’ Shortland Room and the Cardiff Workers would be known to old supporters of Cold Chisel as thoroughly as Diggers might have once recalled the great battles of World War One.

I recite this background only to point out that Cold Chisel and the communities that loved them were the ones to make a change to the culture, not the forces that sought to control things from above – or the industry that belatedly crowned them.

It may seem romantic, but their career was truly a case of the people and their champions going against the grain and winning a meaningful part of themselves back. Even if that victory was only temporary, as victories usually are. The terms of that ferocious bond were simple: speak for us; give us a good time when you play. Stand and deliver.

Take a good look at a video on YouTube of the band performing at what were then the Countdown TV Week Australian Music Awards in 1981. Cold Chisel insisted on playing live, refusing to mime to a pre-recorded track. They did this so they could bust open during their rendition of ‘My Turn to Cry’ to roar out a litany of venues they had built their career on, destroying the stage amid feedback, and rejecting the ceremony with Barnes’ thumping war cry, “And now you’re using my face to sell TV Week!”

The band’s bluesy Led Zeppelin expansiveness, hard-rocking Free and Bad Company influences, and plain-spoken lyrical intelligence – sharpened on the songs of Bob Dylan and slyly sexual, aggressively stripped down ‘50s rock ‘n’ roll songs – were never in easy step with the punk era. Even so, the Countdown TV Week Awards performance was as revolutionary as things got in the Australian music industry. It’s yet to be topped as in-your-face F.U. gesture from a successful band here. Many talk; but few bite the hand that feeds them.

Looking around at the age of the crowd tonight, I’d laughed to myself that there were plenty of rock ‘n’ roll Anzacs here who knew this history. Old and sometimes half-familiar faces who’d come out in force for their band. Even so, I was surprised at how much a good half of the crowd were so young – the children and the grandchildren of the original fans, as well as a measure of Cold Chisel’s iconic songs crossing any generation gaps.

There’s a gratitude that comes with this and, yes, a little nostalgia. Cold Chisel gave me a language and a regard for my world that I might have otherwise lacked as a boy in late ‘70s Newcastle. The connections were there in the band’s outsider postures and poetic observations of working class life; in an apparently simple drinking song like ‘Cheap Wine’ that managed to be celebratory and down-at-heel at once; and, for a Newcastle lad like me, explicitly detailed in a semi-trailer driving anthem like ‘Shipping Steel’, and ‘Star Hotel’, inspired by the city’s famed youth riot over a venue closing and boredom catching fire. I’d lived opposite the BHP and watched loads of steel shipped out and ripping illegally down my street; I’d been a regular at the Star when it was the only place to go in town.

Be it a single line of lyric, or a whole song, Don Walker was open about actively writing for the communities that supported the band, returning each time with new songs that were their way of saying thank you to the crowd. When the protagonist of Khe Sanh talked of wandering “from the ocean to the Silver City”, everybody in Broken Hill knew what town he meant. ‘Breakfast at Sweethearts’ wasn’t a clichéd red-light story of the night, it painted Kings Cross life in its morning-time, aftermath rhythms. ‘Four Walls’ is an object lesson in simplicity, almost an existential gospel song, every line measuring the nature of confinement in gaol, from a sharp mention of the Bathurst riots to the bare contents of a cell, and “calling time for exercise round Her Majesty’s Hotel / The maid’ll hose the room out when I’m gone.”

In short, the band, and Walker especially as its main songwriter, was telling stories about places, people and experiences that no one else was articulating or bothering with.

Tonight, I heard that connection in unexpected ways during ‘Khe Sanh’, the Don Walker-penned tale of a returned Vietnam vet who can’t settle down and find a meaning for his life. For a moment, it was as if the song’s feeling – rather than its story – knew me before I was old enough to fully know myself. Almost forty years after first hearing it live at the Mawson Hotel in Caves Beach, I suddenly found myself able to understand where a wild and restless spirit can wander into eternal loss.

During the song, I was reeled back to memories of being at uni in Newcastle, to my first share house and our neighbour, a Vet whose friendly, but bottled-up energy was something we never knew quite how to handle. I remembered, too, the Anzac Day marches of my childhood, the crowds subsiding into quiet applause when the Vietnam vets came rolling down Hunter Street as part of the parade. This was not as a rejection of them, but an awareness of something deeply wrong. Appearing in a ragged congregation of denim, medals, reflector sunglasses, wild beards, wheelchairs and camouflage fatigues, they flaunted an alien and disorderly image that came from somewhere we could never understand or cover up with false nobility.

Yes, they were back here; but they would never return home all the way. My mother would just shake her head and say, “those poor boys”.

The idea Cold Chisel could give these men an anthem is spell-binding in the truest of ways. Jimmy Barnes would remember Walker working on the song for months, basing it on the conversations he had with two friends who’d fought in Vietnam. Walker finally wandered into rehearsal and told the band it was easy to do, let’s play it tonight. He was keen on it being a punk song, but the band leant towards a country-rock form. Walker knew they were right, adding his Duke Ellington inflected honky-tonk piano playing underneath. Jimmy Barnes had other problems to deal with. “It really was easy for them, because there are not many chords,” he said, “but for me it’s like a novel. I had to learn all the words that day!”

Since then, ‘Khe Sanh’ has become so loved most Australians can sing it more accurately and passionately than our national anthem. And this despite the song being banned from radio for its lyrics when it first appeared due to its very casual references to sex and drugs. What is that draws us as a nation to the abandoned and the damaged, to the prisoner, the dreamer and the underdog? What is it that makes songs like ‘Waltzing Matilda’ and ‘How to Make Gravy’ and ‘Khe Sanh’ and ‘Flame Trees’ maps for who we are? The answer to those questions have a lot to do with not just Cold Chisel’s success, but the kind of love that embraces them.

Tonight, Cold Chisel prove to be rusty and take a few songs to hit their stride. They make more mistakes than they should, and some new arrangements don’t quite gel. To be honest, the start is just a mess. Guest musicians on honking baritone sax, and three backing vocalists (one of whom is Barnes’ daughter Mahalia), don’t always fit in smoothly either. Only Dave Blight, the band’s career-long harmonica player, is able walk on like it was only yesterday. But much like going to see The Rolling Stones or the Sex Pistols, I don’t need Cold Chisel to be professional or perfect, I just want them to be great. And in the true spirit of great rock ‘n’ roll bands they deliver, standing on the shoulders of one giant song after another, fighting for, then roaring into life.

It’s a little melancholy to see Cold Chisel showing their years, aged warriors all. I know from my teenage memories that tonight does not, and can never have, the same raging heat of the band’s early years – and this gives me a stubborn feeling that unless you were there, back then at the Mawson Hotel, there is no way you can understand how great they really were.

But the band has something else in its favour that it has always had, and this has only grown stronger over the years – the love of an audience that sings with them in thanks for every song that now belongs to all of us. Jimmy Barnes and guitarist-singer Ian Moss joke about the crowd going so far as to sing over, and even ahead of them. Once or twice, when Moss or Barnes miss a cue or stumble on a line, the audience keeps them on an even keel. ‘Flame Trees’, ‘Four Walls’, ‘Standing on the Outside’ and ‘Khe Sanh’ feature in this ritual. There is no denying there is power in our union.

Little details and pleasures emerge along the way. In a relatively small venue, the nature of Cold Chisel as a gang is made clear. In the age of ‘toxic masculinity’ it can be too easy to attack notions of ‘mateship’ when its spirit can also serve to enhance ideals like sensitivity, loyalty and communication. It’s one of the great things revealed by watching a fine rock ‘n’ roll band perform on a tight stage like this, each human part locking in to support the other. Male energy; good energy.

The rhythmic Jerry Lee Lewis pound in Don Walker’s piano playing sharpens and pushes. Bassist Phil Small’s subtle, almost jazz-inflected contributions surprise for their deft touch. The way Charlie Drayton has settled in on drums after the 2011 death of founding member Steve Prestwich shows sensitivity even now, almost a decade later, energising the band and keeping things strong without lapsing into hardness or rigidity. Dressed in black, Barnes prowls the stage like some heavy old panther, his scowling and pugnacious stance breaking open like sunlight every time he smiles and pulls the gaze of one band member or another towards him.

Ian Moss stands to one side of the stage as always, a reserved, yet fluid force on vocals and guitar who keeps his lead breaks concise and inside each song’s needs. Once, or twice, a trace of slowness or stiffness in his fingers seems to force an error. Dripping with sweat, he pours onwards again. Barnes’ voice has lost some gravy and sweetness in his voice that will never return. The furious blues and soul spirit of old used to remind me of a rock ‘n’ roll Otis Redding. Nowadays, he makes surprising use of a higher register as his throats loosens, giving words and lines new dynamics and emphases. Any loss of natural ability is compensated by a more thoughtful and experienced singer who still knows how to tear into his moment. If anything, he is singing better now than a decade ago when his voice seemed shot to pieces. As Barnes warms up, the whole band starts rising to their game. Things just get stronger and stronger.

On a night of many highlights it is ‘Wild Colonial Boy’ – Don Walker’s rewrite of the traditional Irish ballad – that stands out for its overwhelming, almost animalistic power. It comes over as the protest song it is, an affirmation of going-down-fighting energy rooted in the bush-ranging past from which it originally stems, reframed by Walker as a present-day working man’s struggle to hold on to his “union card” and take no shit. The rebellion in it seems to grow out of the landscape itself: “I am just a wild colonial boy / My name you’ll never see / I breathe the silence that destroys / All their desperate harmony.”

Barnes becomes that timeless rebel figure, a Robert De Niro figure of sorts to Don Walker’s song-writing Martin Scorsese. The songs are just stories, of course, but they come alive with vivid characters, voices and landscapes that many of us can recognise and even relate to. Barnes old jibe about ‘Khe Sanh’ being like singing a novel is spot on. Each song opens out in the mind like a world. The richness of the lyrics makes Barnes’ commitment even more impressive. He really is the songs when he sings them.

I’m made aware again of an unfashionably male intensity to the music; one that is not without its hints of violence and faintly misogynistic traces. But the overriding energy is romantic, caring, affectionate, and sometimes, redemptive – a case of out of the black and into the blue. It’d be pretentious not to also note that Cold Chisel’s music is intensely engaged with good times, seized hard and held tight. Is it really any wonder the common working class expression for partying is ‘raging’? Raging against the dying of the light.

Another elusive form of hedonism and escape underlines the band’s documents of struggle and defiance. It’s harder to put a finger on. But I’d once asked Don Walker about it in an interview. At the time, I had tried to locate it in the band’s life on the road, the bitumen veins that flowed into their uniquely Australian being: a “c’mon-let’s-roll” energy. Walker seemed to agree, and spoke of how heavily the band had toured up and down the east coast. He saw the highway as an imaginary thread that ran all the way up to Asia, and vaguely alluded to all the drugs and damage, the history and elemental mystery, that had flowed south into our culture after Vietnam. This led Walker to speak of his interest in “a Pacific sound, something that connects Chet Baker, Jane’s Addiction, The Doors, Dragon… there’s a real similarity there, this demonic, exotic, sea children vibe that I like in all of them.”

Walker was always the song-writing engine for Cold Chisel, the lyrical visionary, but tonight affirms Cold Chisel as a genius five-piece, a band of equals creating something bigger than any individual’s contribution. Barnes’ songs, especially ‘You Got Nothing I Want’, have their own pelting, defiant power and stormy, good times imperatives. A contribution from Moss like ‘Bow River’ opens the band’s references to a sweeter sense of landscape than Walker’s burnt-off sugar-cane country inclinations. Phil Small’s ‘My Baby’ is that rare thing, a happy love song, not to mention one of the band’s biggest hits. Every member of this gang adds something to the whole that matters.

After a two-and-a-half-hour set, including two encores, the crowd gives up on forcing another encore and the house lights go up. At the merchandise counter, they are selling T-shirts that mark key venues and dates in the band’s history. Of course, they have one ready for tonight. There’s another that shows a torn front page from the Newcastle Sun graphically depicting a bloodied face from the Star Hotel riot in 1979. I want that T-shirt real bad, but I don’t have the money.

I walk quietly to my car and put on the band’s first self-titled album at banging volume as I turn the ignition over. The opening track ‘Juliet’ leaps from the speakers. I think back to when I was becoming a young man in Newcastle, driving south to the edge of town to see Cold Chisel before they even had a record out, way back when they would play covers like Dylan’s ‘Mozambique’ and The Troggs’ ‘Wild Thing’. I wonder about my old Mawson Hotel compadres like Brad and Dave, and all the others whose names I have lost, the friends who made “my heart sing” as we sat in the carpark drinking and talking after a show, hearing the ocean waves crash into the darkness of Caves Beach.

I wonder where life has taken them all, and about my own life too, and all the feelings prefigured and memorialised inside these songs. And I feel again the native restlessness and tribal loyalties of a working class coastal town that marked itself deep inside my being. As the music plays in my car, I come to an intersection and turn the wheel to see that bird’s wing still stamped on my wrist from when I stepped inside the venue tonight. Then I hit the straight of the road and let my headlights take me home.

Story by Mark Mordue ©

Wicked review of a band I heard a lot about when living in Sydney but never bothered to look up. Here because of the fantastic writing in your latest book. A big fan.

LikeLike

Thanks Mark!

LikeLike